An island nestled in the southeast Mediterranean with a population of around 1.2 million people. An island geographically located in the Levant, or the Middle East or Western Asia depending on where you’re positioned. Our largest city, Nicosia or Lefkosia or Lefkoşa, is the last partitioned capital in the world.

In the south, the Republic of Cyprus serves as one of the EU’s youngest and most easterly members. The north marks the configuration of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus; a de facto state with a population of 320,000 people (a mix of Turkish speaking Cypriots and Turkish settlers) that is currently unrecognised by the international community.

There are two flags, two currencies, two states, and several languages including Greek, Turkish, English, Cypriot Greek, Cypriot Turkish, Armenian, Cypriot Arabic (known as Sanna), as well as Kurbetcha, a Roma Turkish language mainly spoken within communities in the north.

On this divided island, subjugated to shifting powers and longstanding occupying armies from antiquity to the current day, a third flag flutters in some quarters. Britain has been here since the late nineteenth century.

Located in a body of water closer to North Africa than Europe, the British colonial project at the turn of the 1956 Suez Canal crisis recognised why Cyprus was strategically so central to many previous empires – and why the island had to remain under British control, even if that meant suzerainty.

From Cyprus’ military enclaves British and French aircraft took off every sixty seconds in the Suez crisis, bombing and dropping off paratroops over Egypt, in the West’s fight to repossess the canal; a strategy of controlling important resource routes the British would repeat in subsequent conflicts for decades ever after.

Divide and rule

The British, opposed to the 1950s idea of Enosis (a political union between Cyprus and Greece) found themselves in a geopolitical quandary. If a union went ahead, Britain and its allies would lose not only their ‘office’ in the region, but their military launchpad too.

With the appointment in 1955 of Field Marshal Sir John Harding as governor of Cyprus, then still a British colony, the UK set to work to violently suppress the revolts staged by the newly formed Greek nationalist movement EOKA. That movement opposed British occupation, communism and later in 1971, with the forming of EOKA-B, Turkish speaking Cypriots.

In turn, the British meted out punishment in the form of public executions, hangings, enforced curfews, raids, and the construction of internment camps from 1956 to 1959. As fighting escalated between the British, EOKA-A and also the Turkey-backed TMT (Turkish Resistance Organisation), London began to consider plans to divide the island.

Knowing Turkey was the closer ally with military supremacy, British officials thought it might work in their favour if they could convince Ankara of a genuine threat to the security of the Turkish speaking Cypriot minority.

“The British meted out punishment in the form of public executions”

The Americans, cautious not to inflame the situation by aggravating Greece, warned of possible ramifications if they decided to pull out of NATO, or worse still, if two NATO countries went to war. The British decided to let Greece and Turkey pontificate on the fate of Cyprus, and so in a hotel lobby in Zurich in 1959, Greek prime minister Constantine Karamanlis and Turkey’s Adnan Menderes began to sketch out the island’s future.

It was agreed Cyprus would be granted limited independence in a move to circumvent Enosis. The newly drawn-up constitution would allow troops from Turkey and Greece to be based on the island, plus the appointment of a Turkish speaking Cypriot vice-president with powers to veto all legislation if necessary.

The final article became the famous Treaty of Guarantee made between Cyprus, Britain, Turkey, and Greece in 1960. This permitted these powers to intervene in any future conflict on the island if they felt a breach of the settlement had taken place.

In return for facilitating what they considered to be a satisfactory deal, the British rewarded themselves with two sovereign military enclaves in Cyprus – one in Akrotiri and the other in Dhekelia – annexing 3% of the island’s territory.

Even on the summit of Cyprus, at Mount Olympus, Britain kept a spy station that could intercept communications as far away as Zambia. And the island’s north-west peninsula, Akamas, would be used as a UK army firing range until 1999. Once the final treaties establishing the new republic were signed, it appeared more legislation had been devoted to the British bases in Cyprus than to all other provisions combined.

Launchpad

Since independence, the British bases have been used not only to surveil other parts of the region, but to supply weaponry, military assets, fuel and personnel to almost every major conflict without giving notice to Cypriot officials. It’s reported the US were using the bases to deploy troops into Iraq and later Syria which signifies a direct violation of the Treaty of Guarantee.

The RAF also used Akrotiri for surveillance and aerial refuelling missions in the bombing campaign against Libya in 2011. During Saudi Arabia’s brutal bombardment of Yemen, BAE Systems cargo flights refuelled at the base every week while carrying essential spare parts for the Saudi air force.

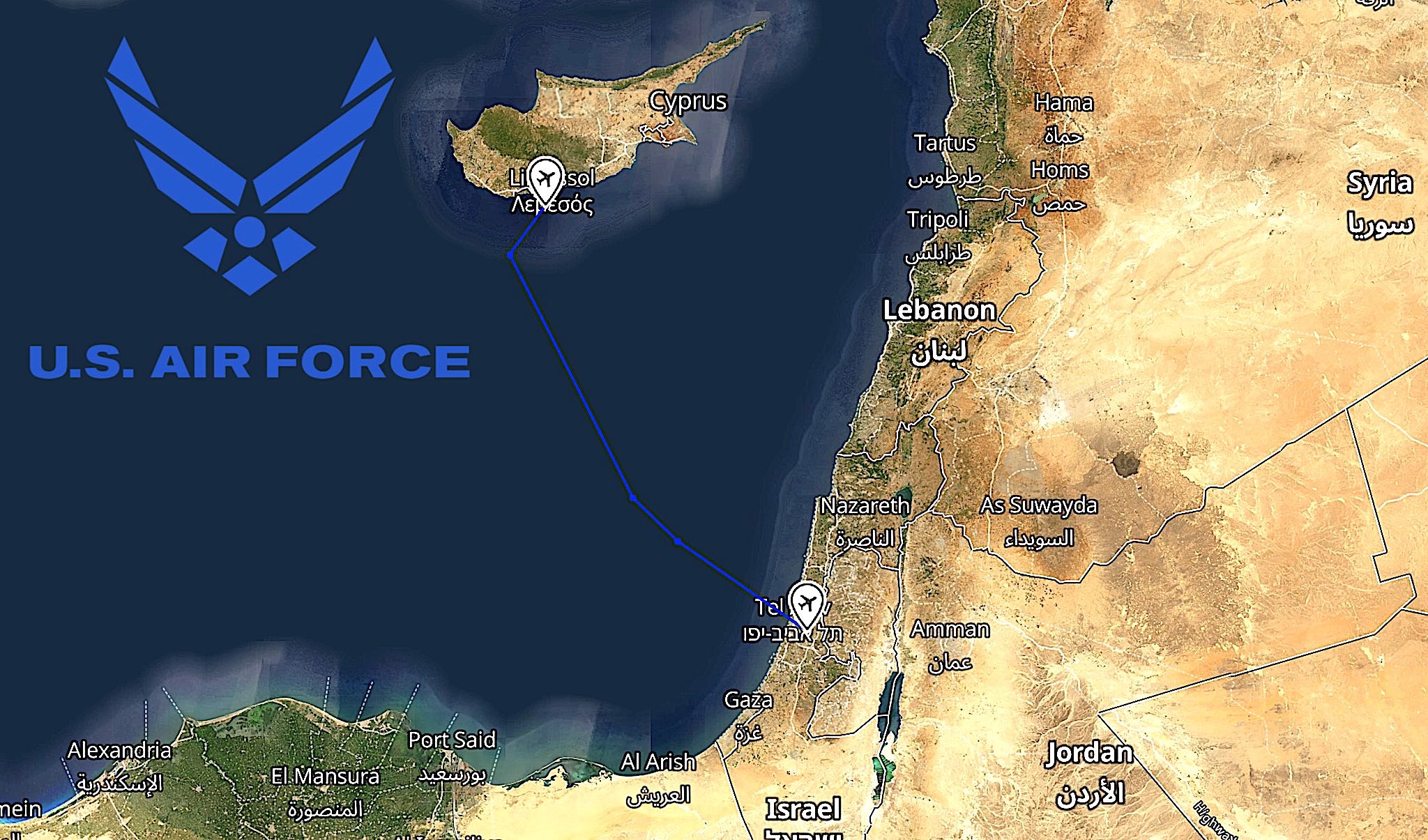

Most recently, Declassified UK and Haaretz reported that America is moving weapons into Israel via the British bases in Akrotiri, with 50% of US flights leaving the area said to be carrying arms. This would again implicate Britain in offering the territory to the Americans without consulting the Republic of Cyprus, and thwart the notion of true postcolonial independence.

President Nikos Christodoulides indicated he had been blindsided by the arms transfers, saying: “There is no such information, our country cannot be used as a base for war operations.” Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar said both communities “will definitely not approve of the island being used as a tool for Israel’s oppression of Palestine.”

AKEL, Cyprus’ main socialist party, has been openly opposed to the bases from their inception. It states: “Territories of our country are used for the carrying out of military operations of third states in our wider region, the promotion of their interests and not for the benefit of the people of Cyprus.”

One of AKEL’s MPs, Giorgos Loukaides, said the flights from Akrotiri to Israel made Cyprus complicit in the genocide in Gaza.

In 2001 over 1,000 Cypriots clashed with riot squad officers amidst plans to erect a radio mast at the Akrotiri base. The mast, considered to be a health risk to the environment as well as local people was met with wide disdain after Cypriot MP Marios Matsakis was arrested for leading the campaign to have the mast removed.

For now, protests in Cyprus against the bombardment of Gaza have been focused on the capital, Nicosia. But it might just be a matter of time before attention turns towards the base at Akrotiri, where Britain directly undermines Cypriot foreign policy and sovereignty.