Nuclear weapons have come back to centre stage with Putin’s putting Russian forces on nuclear alert over Ukraine. The war is not going according to plan and as the Kremlin escalates it to levelling cities, the demand across Europe and beyond for a Nato no-fly-zone is growing.

Putin’s nuclear threat is designed to discourage Nato from implementing any such thing.

For most the idea of fighting a nuclear war seems absurd, the assumption being that a nuclear balance provides stability through ‘mutually assured destruction’.

But this has never been the case.

Since the start of the atomic age in 1945, nuclear arms have been seen by powerful states as useable weapons and appropriate in certain circumstances for fighting ‘limited’ nuclear wars.

This is the case with Nato as an alliance – and individually with the UK and France – so it would be rash to presume Russian nuclear planning isn’t similarly organised.

Indeed, much of the drive behind the new UN Treaty on the Prohibition Against Nuclear Weapons, which already has 56 signatures, was this fear of nuclear instability.

At the start of the nuclear age in 1945, atomic bombs were seen as the direct descendants of the conventional weapons that had been used during the Second World War for aerial attacks on cities such as Dresden and Tokyo, where tens of thousands of people were killed.

By 1948 the United States had an arsenal of 50 atom bombs. Russia tested its first in 1949 and both began to develop the far more powerful H-bomb.

Britain’s tactical nuclear arsenal

The UK came on the scene a little later. It first tested a nuclear weapon in 1952 and by the end of that decade could start deploying its nuclear-capable Valiant, Vulcan and Victor strategic bombers.

These, too, were seen in the context of British involvement in the area bombing of German cities. But Britain was also an early adherent to the idea of fighting limited nuclear wars, an issue particularly relevant in the Middle East and Asia towards the end of empire.

There were nuclear-capable Canberra bombers and nuclear weapons deployed to RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus from 1961 to 1969 to support the Central Treaty Organisation (Cento), the southwest Asian equivalent of Nato. These were replaced by Vulcans in 1975.

From the mid-1960s there were regular detachments of V-bombers to RAF Tengah in Singapore. The Royal Navy also had nuclear-capable Scimitar and Buccaneer strike aircraft on aircraft carriers such as Eagle, Ark Royal, Centaur and Victorious over a 16-year period from 1962 to 1978.

The role of British nuclear weapons was expressed by Harold Macmillan in 1955, when he said: “The power of interdiction upon invading columns by nuclear weapons gives a new aspect altogether to strategy, both in the Middle East and the Far East.”

Macmillan, who was then defence minister, felt such a tactic would afford “a breathing space, an interval, a short but perhaps vital opportunity for the assembly, during the battle for air supremacy, of larger conventional forces than can normally be stationed in those areas.”

Two years, Macmillan’s successor Duncan Sandys said: “Limited and localised acts of aggression, for example, by a satellite Communist State could, no doubt, be resisted with conventional arms, or, at worst, with tactical nuclear weapons, the use of which could be confined to the battle area.”

Acceptable in the 80s

The idea of usable nuclear weapons persisted through the decades and by the early 1980s Britain’s nuclear arsenal had grown to several hundred warheads.

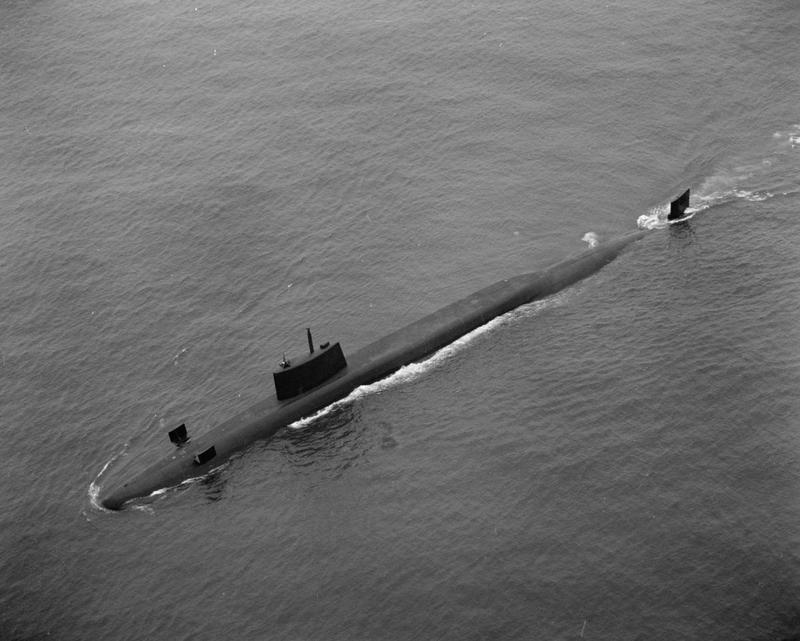

At the strategic level there were the Polaris submarine-launched nuclear missiles. At the shorter-range tactical level there was the WE177 bomb that could be delivered by the RAF’s Buccaneer, Jaguar and Tornado strike aircraft.

The Royal Navy had Sea Harrier aircraft for the WE177 and helicopters to carry an anti-submarine variant. Even a helicopter flying from the Navy’s smallest frigate, the Type 21, was nuclear-capable.

Britain’s arsenal did not even end there, as four different US nuclear warheads were available for use under a dual control system.

One was a nuclear depth bomb carried by Nimrod maritime patrol aircraft; another was carried by the army’s short-range missile; and the final two were nuclear shells to be fired from 155mm or 203mm artillery.

With the end of the Cold War most of these were withdrawn in the 1990s, leaving the UK with just the Trident submarine-launched missile system.

That, though can be fitted with either of two warheads, one for massive strategic use and the other a much lower-powered warhead but still nearly as destructive as the Hiroshima bomb.

Then there was Nato

How does all this fit in with Nato? As one of the founding members of the alliance, Britain was involved in the alliance’s nuclear planning from the mid-1950s.

In that period, Nato nuclear policy was codified in document MC14/2, known as the “tripwire” policy which planned a massive nuclear response to the initiation of war by the Soviet bloc.

By the latter part of the 1960s, the Soviet Union had developed its own array of tactical systems and Nato responded by modifying the “tripwire” and developing what it called a “flexible response”.

This envisaged the limited use of mostly low-yield warheads early in a conflict against Warsaw Pact troops in the belief that they might be “stopped in their tracks”. If that failed, a more general nuclear response might ensue.

Britain was very much part of this move. Its nuclear forces were normally committed to Nato and UK personnel played significant roles within the alliance’s Nuclear Planning Group.

This move away from deterrence through mutually assured destruction was rarely publicised by the British government.

It was not until two decades later that the Ministry of Defence told parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee:

“The fundamental objective of maintaining the capability for selective sub-strategic use of theatre nuclear weapons is political – to demonstrate in advance that Nato has the capability and will to use nuclear weapons in a deliberate, politically-controlled way with the objective of inducing the aggressor to terminate the aggression and withdraw.”

First use

Nato was not just prepared to use nuclear weapons first in response to a conventional military attack from the Soviet bloc. It was willing to do so at a much earlier stage in such a conflict.

The Supreme Allied Commander of Europe, General Bernard Rogers, said in 1986: “Before you lose the cohesiveness of the alliance – that is, before you are subject to (conventional Soviet military) penetration on a fairly broad scale – you will request, not you may, but you will request the use of nuclear weapons”.

The General’s comment chimes with what I was told by a senior German civil servant during a briefing for academics at Nato headquarters in the late 1980s. This man, who was seconded to the alliance’s Nuclear Planning Group, described with some enthusiasm a circumstance of potential first use.

If Soviet forces crossed the frontier into West Germany, he said an immediate and valid response would be to detonate up to five low-yield high-altitude nuclear warheads. This would be sufficient to cause the Soviets to halt their advance but insufficient to inflict widespread damage.

He really seemed to believe it would work.

‘Out-of-area’ operations

Britain has also been willing to use its nuclear arsenal in ‘out-of-area’ operations, in conflict with countries far from Nato’s borders.

After Argentina occupied the Falkland Islands in early 1982, Margaret Thatcher dispatched a substantial naval task force. Six days after it left Britain, the Observer reported that: “It is almost certainly carrying tactical nuclear naval weapons – atomic depth charges carried by Sea King helicopters and free-fall bombs carried by Harrier jump jets – as part of Nato equipment.”

Later reports indicated that nuclear weapons from two destroyers were transferred en route to an auxiliary supply ship and the two aircraft carriers, Invincible and Hermes.

Declassified recently revealed that British ships carried 31 nuclear depth charges during the Falklands crisis. The weapons remained on the Task Force during the war and there were also multiple if unconfirmed reports that the Thatcher government was prepared to deploy a Polaris missile submarine to the mid-Atlantic to bring it within range of Argentina.

Nine years after that war, the UK government committed substantial forces to a US-led multinational coalition to evict the Iraqi forces that had invaded and occupied Kuwait in August 1990.

There was considerable concern that Iraq had a useable arsenal of chemical weapons. A senior British army officer attached to the 7th Armoured Brigade which was leaving for the Gulf clearly indicated Britain was willing to retaliate with nuclear weapons.

He confirmed that an Iraqi chemical attack on UK forces would be met with a tactical nuclear response. Similar threats were made at the onset of the 2003 Iraq war.

Deliberate ambiguity

After the end of the Cold War, Conservative prime minister John Major scaled down Britain’s nuclear arsenal in a series of unilateral moves.

He ceased deployments of dual-control US nuclear artillery and missiles, and withdrew the WE177 tactical nuclear bombs and depth bombs between 1992 and 1998.

But in order to preserve a British ‘sub-strategic’ capability, a low-yield variant of the standard high-yield Trident thermonuclear warhead has since been deployed.

There was a period from the early 1990s to 2010 when successive governments, both Conservative and Labour, were fairly open about the size of the UK nuclear arsenal, including plans to decrease the overall arsenal.

That ended a year ago with a new policy announcing an increase in the number of nuclear warheads for the Trident submarine fleet.

The new UK policy also threatens to use nuclear arms against non-nuclear weapons states that are said to be heading in the direction of acquiring nuclear weapons — or, as the government puts it, those states judged to be “in material breach of [their] non-proliferation obligations”.

A generic description of the UK nuclear posture previously appeared in successive defence white papers. The 2015 statement stated: “Only the Prime Minister can authorise the launch of nuclear weapons, which ensures that political control is maintained at all times. We would use our nuclear weapons only in extreme circumstances of self-defence, including the defence of our NATO Allies.”

It added: “While our resolve and capability to do so if necessary is beyond doubt, we will remain deliberately ambiguous about precisely when, how and at what scale we would contemplate their use, in order not to simplify the calculations of any potential aggressor.”

Low-yield warheads

That still leaves the issue of under what circumstances might the UK initiate the first use of nuclear weapons. Successive British governments have studiously avoided speaking in specific terms.

However, a useful guide to the low-yield warheads in the Trident programme was published in the mainstream military journal, the International Defence Review in the mid-1990s, and also fits in with Nato’s nuclear posture.

This noted that: “At what might be called the ‘upper end’ of the usage spectrum, they could be used in a conflict involving large-scale forces (including British ground and air forces), such as the 1990-91 Gulf War, to reply to an enemy nuclear strike.”

“Secondly”, it noted “they could be used in a similar setting, but to reply to enemy use of weapons of mass destruction, such as bacteriological or chemical weapons, for which the British possess no like-for-like retaliatory capability.”

And “Thirdly, they could be used in a demonstrative role: i.e. aimed at a non-critical uninhabited area, with the message that if the country concerned continued on its present course of action, nuclear weapons would be aimed at a high-priority target.

“Finally, there is the punitive role, where a country has committed an act, despite specific warnings that to do so would incur a nuclear strike.”

The options outlined here fit well with what is implied in Nato’s flexible response strategy and relate to Britain’s view of the potential role of nuclear weapons that goes back to the 1950s.

What is striking is that three of these options noted above involve the first use of nuclear weapons, and the final two are uncomfortably close to the threat implied by Vladimir Putin on 27 February 2022.

If the Ukraine crisis ends soon and an even more devastating conflict is avoided, an immediate priority must be facing up to the issue that many states regard nuclear weapons as useable.

Being serious about the UN nuclear weapon ban and joining those many states that have already signed up would be a very good start.