Read in Arabic on Muwatin

A British mercenary used a bayonet to puncture the windpipe of a 20-year-old rebel captured in Oman. The victim, Mohammad al-Adid, was stabbed during a brutal interrogation, which saw him stripped naked, head shaved, legs chained and thumbs tied together behind his back.

Al-Adid survived the assault in 1966 and pressed charges against his interrogator Captain Thomas Stanley Baxendale, who spent two months confined to base awaiting a court martial. The mercenary was found guilty of misconduct and dismissed from the Sultan of Oman’s private army, avoiding a custodial sentence.

British diplomats in the Gulf were aware of the incident, which should have been classed as a war crime, but successfully managed to keep it under wraps. Baxendale spoke to Reuters news agency after he was deported from Oman but their journalists did not publish a story, regarding him as “a bit of a ‘nut case’.”

The incident took place a month after the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for UK troops to leave Oman. Hundreds of British men with military and colonial policing experience were hired by Oman’s Sultan Said bin Taimur in the 1950s and 60s.

These ‘contract officers’ helped the despotic ruler to suppress his own people and conquer new territory, at a time when Oman was effectively a British protectorate and its army was led by a UK military veteran.

There have long been allegations of abuse against these mercenaries, but the Baxendale case contains some of the clearest evidence of torture. Multiple witness statements detailing his cruel, degrading and inhumane conduct were taken from his colleagues, showing it was shocking even among his peers at the time.

Declassified shared its findings with Nabhan Alhanashi, an exiled activist who runs the Omani Centre for Human Rights. He commented: “This horrific incident is evidence of the involvement of British mercenaries in establishing the foundations of a criminal regime represented by the Sultan’s Al-Busaid dynasty, which survived a popular revolution against it because of the British.”

Imperial enforcer

On a stack of audio cassettes at the Imperial War Museum in London, Baxendale can be heard talking about his colourful career as a colonial policeman. His northern accent is punctuated by heavy coughing and a sneering tone, as he seems to puff his way through the three hour interview.

He spent so much time patrolling Britain’s empire – where the sun never set – that his face was marred with skin cancer by the time the tapes were recorded in 1990 as part of an oral history project.

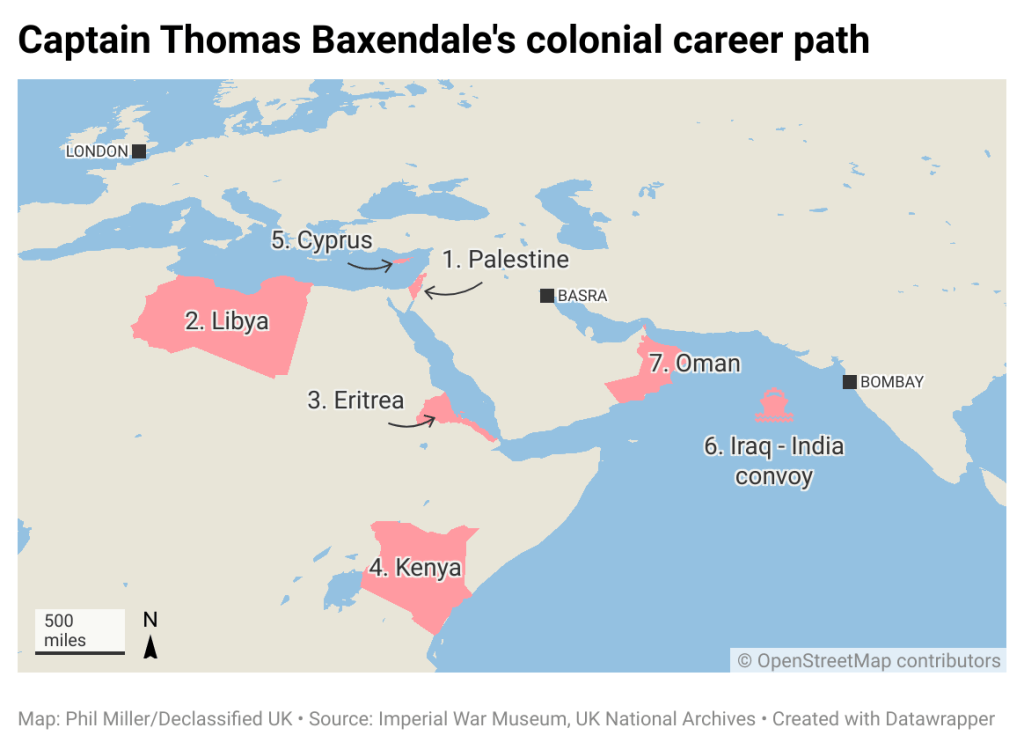

They give a selective account of his past, carefully omitting his brushes with the law that are catalogued in newspaper clippings and government files. Everyone agrees though that Baxendale cut his teeth as a colonial policeman in Palestine in the 1940s, where he helped deal with insurgencies against British rule.

“It was quite a good life”, he reflected, detailing his “frequent” experience of arresting suspects for trial by the military, where they faced the death penalty. “It would be a good idea to use military courts in Northern Ireland,” he commented to the museum’s interviewer, referring to the IRA. “You probably have to delete that.”

After Palestine, he was later deployed with imperial security forces to Libya and then Eritrea, where he dropped phosphorus grenades from a plane onto cattle raiders during the British occupation. In the 1950s he served as a colonial police inspector in Kenya and was involved in negotiations with high profile political prisoners, including future president Jomo Kenyatta, who he said was “very sullen”.

Baxendale was prepared to “put a tube down their throat” and force feed Kenyatta and his comrades if they went on hunger strike, a move which was averted. He regarded the Mau Mau rebel movement – which was fighting British control over the country – as “absolutely appalling”, dismissing their members as “wiley jokers” with “nefarious and evil ends.”

It is not known if Baxendale participated in any torture of Mau Mau suspects, although their mistreatment was so widespread that the British government eventually had to apologise and pay millions in compensation under David Cameron’s premiership.

Cyprus uprising

In 1955, Baxendale moved to police yet another British colony, Cyprus. He arrived in the midst of an uprising by the Greek nationalist EOKA movement, whose supporters pelted his men with Molotov cocktails.

“I opened up with tear gas and that was adequate,” he reflected, referring to an incident in the Cypriot capital Nicosia. “I didn’t have to open fire but I would have done.” His conduct made the front page of the Daily Express, which said he “saved the day”.

Amid clouds of tear gas, the newspaper’s correspondent watched admiringly as Baxendale led “baton charges against the mobs…soft-hated and armed only with a loud voice.” An army officer marvelled at how Baxendale’s “wonderful” efforts had an “incredible” impact on police morale.

“I opened up with tear gas and that was adequate”

A month later, Baxandale was once again leading the charge to maintain British rule on the Mediterranean island. More than 200 rioters were rounded up and 37 injured.

Yet there are signs Baxendale was overly zealous. In November 1955, the Daily Telegraph reported that he had been accused of striking two Cypriots and would face trial. The outcome of that case is unknown, but Baxendale did admit ominously on the tape recording: “I have a very bad temper”.

‘Living in the 15th century’: Oman

By the end of the decade, much of Britain’s formal empire lay in ruins and Baxendale was left adrift. “I came home from Cyprus and I was in the wilderness for one or two years, no jobs going,” he admitted. “But there was an organisation run by the Foreign Office for ex-colonials. Not just the police. Administration, judiciary, agricultural – all departments. And the object was to find suitable posts for these chaps”.

Baxendale was chosen to provide security on a P&O-owned mail ship that sailed from India to Iraq. A passenger vessel on the same route, MV Dara, had previously been sabotaged and sunk in the Persian Gulf, killing hundreds onboard. The perpetrators were rebels in Oman, a de facto British colony with Sultan Said bin Taimur as a client ruler.

“It was a nationalist movement: Get rid of the Sultans and so on,” said Baxendale of Oman’s rebels. “Their main grievance, I suppose one would call it, was that they were living in the 15th century”. The country “was quite mediaeval” and their Sultan “wouldn’t allow them radios, a very popular item”, Baxendale observed. Football and eyeglasses were also banned, and there were almost no schools or hospitals.

Yet this did not deter Baxendale from engaging with the Sultanic regime, which still permitted slavery. “The second in command of the Sultan’s armed forces in Oman was Colonel Colin Maxwell, who I’d served with in Eritrea and was also ex-Palestine police,” Baxendale explained.

“And one fine day he came on board the ship to see me when we called in [Oman’s capital] Muscat and asked me if I’d like to join the Sultan’s armed forces on the intelligence side.”

Baxendale agreed to become a mercenary, paid to serve in the military of a foreign power. He was given the rank of captain and told to monitor the flow of weapons into the breakaway southern region of Dhofar.

“Oh it was very backward, very backward down there. Very backward indeed,” Baxendale recalled. Unlike later operations when British troops would claim to win ‘hearts and minds’, he said: “We didn’t go in for that in those days”.

His job included interrogating suspects. “Sometimes they’d be quite straightforward but nine times out of ten they weren’t,” he said with a laugh, in one of his last remarks to the tape recorder.

Foreign Office files at the National Archives in London are needed to trace the rest of his time in Oman. This is the first time their contents have been reported by the media. A diary entry, seen by diplomats, detailed his rigorous routine: “I was working flat out, anything up to 18 hours a day. And on two occasions I was on my feet for 36 hours at a stretch.”

Baxendale, who was earning 1,400 Indian Rupees a month (now worth around £1,146), told a colleague he was “enjoying myself, tremendously”. But a few days later, he was medically evacuated to headquarters “suffering from a nervous breakdown”.

During the evacuation, he told a Royal Air Force doctor of a recent nightmare where he murdered a fellow soldier with a knife. The medic remarked he might be a security risk. Maxwell, the Sultan’s deputy commander, said he seemed “strung-up mentally”.

The interrogation

On 20 February 1966, Baxendale was examined by the camp doctor who “formed the impression that he was under considerable mental strain.” The physician advised him to rest completely for a week.

Instead, an intelligence officer, Major Malcom Dennison, tasked Baxendale with questioning a “hard core Dhofari prisoner” the very next day. The detainee was Mohammed al-Adid, who Dennison supposedly thought “might break under interrogation”.

Baxendale was instructed “not to mark the prisoner – but the odd broken finger did not matter.” A British major had already “worked on him for ten days at one stage” and “beat him up”.

Yet worse was to follow.

In the absence of any proper interrogation facilities, Baxendale took the prisoner to his room for questioning. A sworn statement given under his full name, Mohammad bin Taher bin Alawi al-Adid Sayed, describes the sadistic treatment.

“He said al-Adid’s testimony was untrue and threatened to beat and kill him”

The prisoner cooperated during the first ten hours of questioning, but Baxendale lost his temper near midnight. He said al-Adid’s testimony was untrue and threatened to beat and kill him. Drinking from a bottle of whisky, he spat in the prisoner’s face, slapped him and insulted his religion.

A local soldier was ordered to wedge and twist a rifle between Mohammad’s legs, then make him stand by a wall with his thumbs tied together painfully behind his back with a rubber band. He was left in this position “for some time” during an all night interrogation that went on until nearly 5am.

Baxendale regarded this phase of questioning as the “soft approach”.

By now, the mercenary had formed the view that al-Adid “should be broken as soon as possible” as he “holds the key to an underground movement stretching from Cairo to Baghdad”. In reference to Egypt’s pan-Arabist president, Baxendale said “Nasser intends to destroy British influence in the Persian Gulf” and was supporting Dhofari rebels to that end.

He believed their target was “the death of the Sultan and the destruction of the Sultanic Government” and they “will use any means to achieve their aims”. Al-Adid had to sign statements, which were repeatedly torn up by Baxendale who dismissed them as “all lies”.

Torture

Between interrogation sessions, Baxendale drank two double whiskies at the mess before inviting a drinking buddy back to his room. Al-Adid was waiting for them, standing up against a wall with his hands tied behind his back and legs shackled.

As they had a nightcap of around half a bottle of whisky, Baxendale reportedly said: “don’t bother about him, he has been there all day.” His friend commented: “We talked together ignoring the Arab.”

Baxendale then resumed questioning and shouting at al-Adid. He took a bayonet and told the prisoner: “I will kill you if you do not say the truth”. He slammed the bayonet into a table several times and asked his friend to sharpen it.

He ordered another soldier to remove the prisoner’s vest, before using his own camel stick to strip al-Adid’s robe. The prisoner was left standing naked for 15 minutes as his clothing was burnt in a bucket. Blows to the head followed, including from a rope. Dirt was thrown in his face and his moustache shaved off.

Baxendale then “suddenly jumped up shouting at the prisoner” and stabbed al-Adid in the throat with a bayonet. The wound was an inch deep, puncturing his windpipe. One witness “looked up and saw a trickle of blood coming from the prisoner’s throat.” Baxendale supposedly said “I am sorry…I did not mean to do that.” Another witness says he dismissed it as “only a scratch”.

His drinking buddy then put a plaster of al-Adid’s neck and draped him in a sheet. The victim became dizzy and was told to lie down. Baxendale remarked to a local soldier: “Don’t worry. I am not drunk – I am sober. Nothing will happen to him. He is alright, but he is a traitor and I must get to the truth.” He then went off with his friend to drink beer.

When Baxendale came back around an hour later, he ordered the prisoner’s head to be shaved and doused with Dettol, before spraying his face with insecticide. Al-Adid then recalls being made to stand outside in the rain. A guard was told to pour more water over his head.

Operating theatre

Around two o’clock in the morning, the camp’s most senior doctor was woken and summoned to Baxendale’s room. There, the captain, looking “emotionally upset…pointed to an Arab prisoner who was sitting on the floor, and said ‘he fell on a sharp stone and hurt his neck’.”

The doctor saw blood “oozing” through a plaster on al-Adid’s neck and demanded to take him to the base’s medical centre. Once in the operating theatre, with Baxendale still present, the doctor treated the neck injury.

Baxendale rejected medical advice to keep the prisoner in hospital, worried that he would talk to other prisoners. Instead he was put on a bed in Baxendale’s room and told to write further statements, one of which was torn up.

Eventually Dennison, the fellow intelligence officer, intervened on the fourth day and collected al-Adid. “The prisoner got up from the bed with some difficulty,” Dennison recalled. “The prisoner had chains round his ankles; that is normal…I did not notice any injury on the prisoner. He appeared very tired.”

The doctor examined him again in the cells and found a “second degree burn on the forehead, face and chest caused by some corrosive.” There were also multiple abrasions and bruises to his stomach, chest and legs.

Charged

Baxendale was charged with assault and confined to the base as the camp’s commanders wondered what to do with him. Initially they wanted him to leave Oman immediately, but the Sultan “could not have the accused bundled out of the country” and instead ordered a court martial.

He was examined by doctors and was able to instruct a solicitor in Chorley, Lancashire. The mercenary protested that he was under “unlawful arrest”, claiming he had sworn no oath of allegiance to the Sultan, and was only serving in Oman’s army with permission of the British crown.

Britain’s Consul-General in Muscat, Bill Carden, monitored the case, noting: “It has been suggested he was temporarily unbalanced owing to strain of military duties in Dhofar.” The diplomat advised: “The more closely the treatment accorded Baxendale can resemble that which he would get if he were an officer in the British regular forces being tried by Court Martial, the better”.

Carden, anxious to protect the allure of mercenary work, felt a fair trial would be “the best safeguard against the recruitment of contract officers falling off.” A fortnight after the incident, the Foreign Office received “a written invitation to exercise jurisdiction” over the case from the Sultan.

The department expressed “our reluctance to draw attention to it in a case of this kind”, as it would signal British mercenaries in Oman’s army were actually operating under authority from Whitehall. Instead, they hoped the court martial could be dealt with between British officers in Oman’s army, who they presumed would give Baxendale a fair trial.

There remained a worry that if Baxendale was convicted and sent to Oman’s notorious Fort Jalali prison, “where conditions would be poor by Western standards and about which Amnesty International have been campaigning.” The Red Cross was banned from entering Fort Jalali, which Amnesty described as a “dungeon”.

If imprisoned at Jalali, diplomats fretted the case “may embarrass us and reduce the readiness of British subjects to serve on contract in the Sultan’s Armed Forces.” Again, protecting the supply of mercenaries for Muscat was of paramount importance.

Court martial

Left in legal limbo until the end of March, Baxendale plotted an escalation, threatening to renounce his British nationality and alert the Red Cross. The Foreign Office decided their consul could only try the case if the Sultan agreed to create a specific legal exemption, to avoid setting a precedent.

An “Exchange of Letters” between Muscat and London in 1962 had contained a confidential section that allowed Britain to extend its legal jurisdiction in Oman with the Sultan’s consent. An official stressed “the important political consideration that we would not wish to draw attention to our jurisdiction, particularly in a case of this kind involving a British officer and a rebel prisoner”.

Another diplomat warned: “This will, I fear, be grist to the mill of the United Nations and those who attack us over Muscat, on the grounds that the exercise of our jurisdiction is a further demonstration that the Sultan is nothing but a British puppet”.

The Consul-General visited the Sultan in mid-April and received an assurance Baxendale would not serve time in Jalali prison. After this, the UK consented to a court martial being held by British officers serving in Oman’s army.

A fellow soldier asked by Baxendale to prepare his defence accepted that “there can be no denying that Baxendale did wound the prisoner”, conceding the evidence was “quite clear on this point”. However in mitigation he would highlight Baxendale’s mental condition, implying he should not have been assigned the interrogation.

‘Strong recommendation for mercy’

Baxendale was found guilty on 21 April 1966, although the exact charge is not specified and could have ranged from misconduct to assault. He was “dismissed with ignominy” with a “strong recommendation for mercy”. The court’s three man panel included two officers who had won the military cross, the second highest award for gallantry.

Carden was able to observe much of the hearing and regarded it as a fair trial. He reflected: “If the court erred, it was due to their sympathy with Baxendale.” While Carden noted the extenuating circumstances surrounding Baxendale’s state of mind, he added “there were also aggravating circumstances inherent in the manner in which he carried out a prolonged interrogation”.

Some of the witnesses also “did not substantiate the doubts about his mental balance: they did the opposite.” The accused would have faced up to five years imprisonment if he had appeared before Carden in a consular court.

“If the court erred, it was due to their sympathy with Baxendale”

Instead, Baxendale served no jail time. By the end of April, he had flown out of Oman and arrived in Bahrain. By mid-May 1966, Baxendale appeared to be back in England where he spoke to his solicitor and thanked the Consul for his “invaluable help and assistance”.

Another diplomat commented: “As far as I know there has been no publicity for this incident and I hope that we may now have heard the last of it.” In fact, Baxendale had spoken to two or three reporters from Reuters at the Speedbird Hotel in Bahrain.

The mercenary had “given a vivid description” of his prosecution, “but, as they all thought he was a bit of a ‘nut case’, none of them filed a story.” The incident would remain untold for almost another half a century.

Declassified has been unable to contact Baxendale for comment and it is likely he has passed away given the passage of time. The law firm he instructed in Chorley said they were no longer in contact with the solicitor involved with his case.

Pattern

The ramshackle nature of Baxendale’s interrogation techniques might make it easy to dismiss the incident as a one-off: the actions of a rogue, mentally damaged man. Yet five years later, serving British soldiers in Oman would deploy their own, more refined torture techniques, suggesting such behaviour could be officially sanctioned in the right circumstances.

In 1971, a group of 35 detainees were tortured by British forces in Oman. The methods were aimed at extreme sensory deprivation, which would leave no physical scars. Bags were placed over their heads for hours on end as generators churned out deafening noise. Meanwhile, they were forced to stand in painful stress positions.

The longest session lasted three and half days. One man’s interrogation was only stopped because he was assessed “as being so mentally retarded there was no point in questioning him further.”

At least some of the men are thought to have come from the northern region of Musandam, the opposite end of Oman to Dhofar where Baxendale was stationed – indicating how far resistance to the Sultan had spread.

Such techniques are still taught to specialist British troops today on ‘escape and evasion’ courses – to prepare them for being captured by a brutal enemy. Prince Harry, who attended the course lest his helicopter was seized by the Taliban, wrote in his memoir Spare: “Much of what they did to us was illegal under the rules of the Geneva Convention…two other soldiers in the exercise had gone mad.”

In Oman, little has changed politically. Although oil wealth has paved the way for infrastructure spending, all political parties are banned and there is no free press. Corruption appears rife, with the regime acquiring at least £80m of luxury property in the UK.

The Sultan’s family remain in charge, with extensive back up from the British military and intelligence agencies. Despite calls from the UN in the 1960s to remove army bases from Oman, Britain has doubled down, opening a series of new sites there in recent years to house aircraft carriers and test fire tanks.

When activists rose up during the 2011 Arab Spring, they reported being subject to similar interrogation techniques by local police as their predecessors had witnessed in 1971. As long as Oman remains a Gulf autocracy, Britain’s legacy of torture is likely to live on.