If Nicola Sturgeon’s Scottish National Party (SNP) wins a decisive victory at Holyrood this week, she is expected to use the result as a mandate for a fresh referendum on independence.

Breaking away from Westminster would give Scotland the chance to rejoin the European Union after being forced out against its will, but the new foreign policy possibilities do not end with the well-worn debate over Brussels.

Just as important for many Scottish voters is the issue of nuclear disarmament, which could affect Scotland’s position in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) and the UK’s permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.

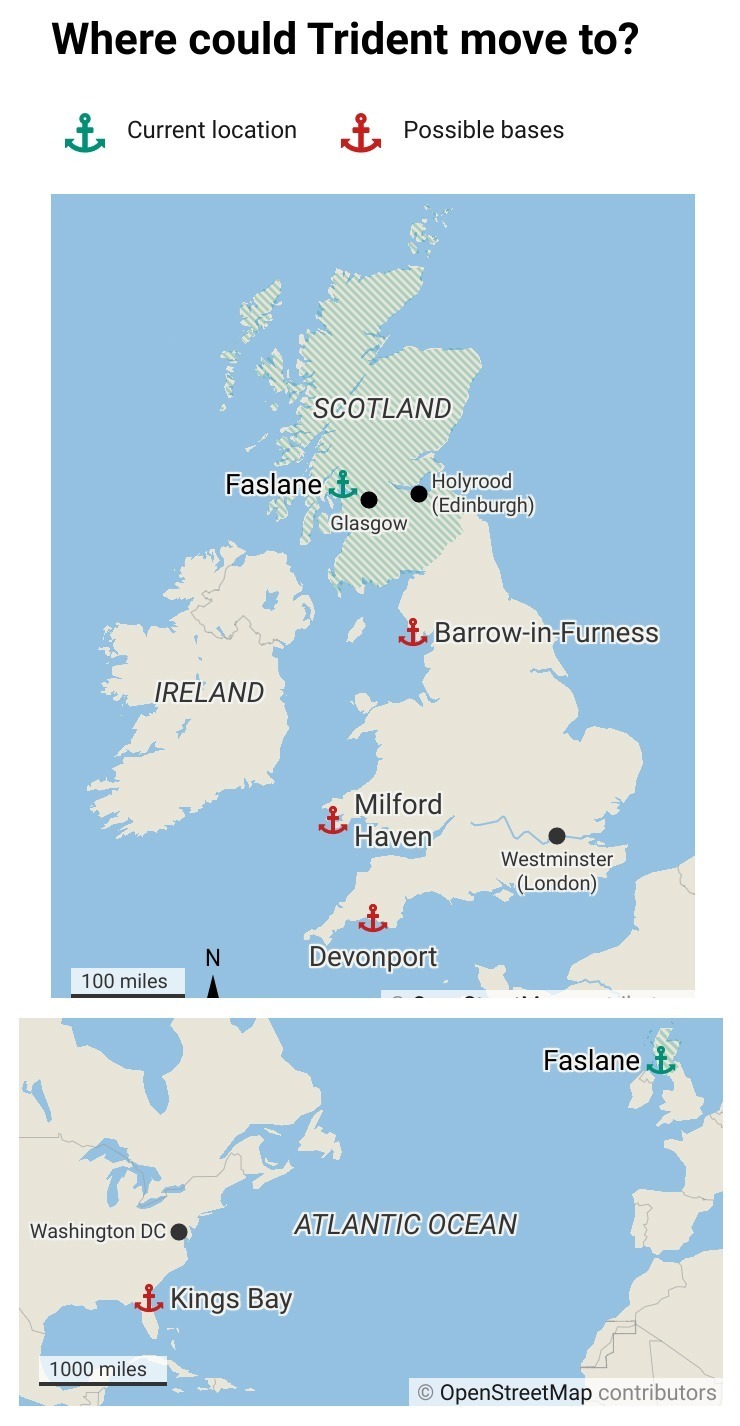

Britain’s nuclear arsenal, known as Trident, is based on the River Clyde at Faslane submarine base, 40km from Glasgow. The proximity of Trident to Scotland’s largest city is a lightning rod for pro-independence parties like the SNP, Greens and Alba.

“I live well inside the blast radius were there to be a strike on Faslane or a disaster there,” commented Ross Greer, who became the youngest Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) when he was elected at the age of 21. He is currently external affairs spokesman for the Scottish Green Party.

“The proximity of the base to our major population centres is a very practical issue of concern,” he said. There have been more than 500 safety incidents with nuclear submarines at Faslane since 2006, according to Scottish investigative website The Ferret.

Aside from the safety fears, Greer believes nuclear disarmament resonates with Scots in other ways. “Trident is such a tangible symbol of a government imposing its will on a country that doesn’t want it,” he told me.

The cost of nuclear weapons, which could exceed £200-billion, led pro-independence campaigners to use the Scots slogan, “Bairns Not Bombs”, arguing the money would be better spent on children.

“The movement for Scottish independence is in a significant part motivated by a desire to be like a normal European country playing a responsible role in the world,” Greer explained. “We don’t have this desperate need to be a superpower.”

If an independent Scotland decided to scrap nuclear weapons, it is unlikely the submarines could simply sail to another base in England or Wales. “You need a very deep sea coastal area and they’re extremely limited – the ones that there are, are all marinas down on the south coast,” Robin McAlpine from the Common Weal think tank in Glasgow told me.

“You’d basically need to clear out a load of millionaires’ yachts and site a nuclear base right in the middle of an affluent middle-class southern community. And it would take 20 years to build the infrastructure – they’re unlikely to be given that by an independent Scotland.”

David Mackenzie, a retired school teacher and assistant secretary at the Scottish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), said research by his organisation and the Ministry of Defence broadly agreed on the lack of alternative harbours in Britain.

“The general received wisdom is that if the UK wished to keep a continuous at sea so-called nuclear deterrent they would have to locate it in Kings Bay”, home to the US navy’s submarine fleet in Georgia. “That’s the only viable option,” Mackenzie commented, calling such a move an “enormous political step” which would “rip off any disguise about the British system being in any way independent [from the US]”.

Land-based or aircraft delivered platforms pose their own substantial problems, leading Mackenzie to believe that “if Scotland became independent and if we stuck by our aspiration to get rid of the nuclear weapons, then the UK would be de facto disarmed. That’s actually a colossal thing in the best sort of ways… the tail wagging the dog.”

‘Post-imperial identity crisis’

There are other possible ramifications of nuclear disarmament. It could also cost Britain its permanent seat at the UN Security Council, which comes with a much-prized veto power over draft international resolutions.

“If you believe Tony Blair, the UN seat has been the big factor in maintaining the nuclear weapons,” Mackenzie commented, referring to comments made by the ex-prime minister in his memoirs that disarmament would be “too big a downgrading of our status as a nation”.

Mackenzie added: “The enormous loss of face generally for the remnant UK, psychologically that’s going to be very difficult for them to swallow.”

The Scottish Greens agree with CND that nuclear disarmament will affect wider UK foreign policy. “Trident is a symbol of the post-imperial identity crisis that the British state is still going through,” said Greer, who is best known for his trenchant criticism of Winston Churchill’s colonial record in a fiery debate with TV host Piers Morgan.

“Britain is not an empire any more and if it didn’t have these nuclear weapons it really wouldn’t be a superpower. And not only are we okay with that, we are actually very happy with that. We would see it as a positive, good outcome for the world if Britain was no longer a superpower.”

Such views are not confined to Greer’s younger generation. “Unilateral nuclear disarmament runs deep within the soul of the Scottish independence movement,” commented Kenny MacAskill MP, who joined the SNP in the 1980s and came to prominence through its left-wing caucus.

MacAskill, a former justice minister who was responsible for Scotland’s prisons and police, told me: “The rise of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament almost mirrors the rise of the SNP.” He said that scrapping Trident “would help break almost a mental attitude in the UK that they have to have the nuclear capability to be able to fly the flag. It’s about England coming to terms with itself”.

Within Whitehall and the London media, support for Trident is so sacrosanct that Jeremy Corbyn had to drop his life-long support for unilateral nuclear disarmament when he became leader of the Labour Party, omitting the policy from its manifesto.

Yet opposition to Trident is mainstream among the Scottish independence movement, giving their supporters a different perspective on Britain’s global role.

“England is a great country with a lot to be proud of,” MacAskill commented. “It doesn’t have to have a delusion about still being a world superpower when it clearly isn’t.”

MacAskill has recently moved from the SNP to Alba, a new pro-independence party led by Scotland’s former first minister, Alex Salmond.

Alba has a different strategy to the SNP on relations with Europe, warning that re-joining the EU could take time and suggesting Scotland should instead prioritise a quick entry into the European Free Trade Association, a smaller block of non-EU members like Norway and Iceland.

Alba’s more cautious approach to the EU may appeal to some Scottish nationalists who are angry with Brussels over its support for Spain’s crackdown on Catalan separatists.

On nuclear weapons, however, the two parties share the same policy. “Our position in Alba is actually the same as the SNP: unilateral nuclear disarmament, Trident needs to be removed from the Clyde,” he said.

Guantanamo option

Despite this shared anti-nuclear platform across Scotland’s three main pro-independence parties, there are concerns about whether such an ambitious policy is actually deliverable.

In 2012, when MacAskill was in the SNP, he helped the party drop its long-standing opposition to Nato, a Cold War-era alliance whose strategic doctrine permits a first strike nuclear attack on Russia.

The SNP’s policy change was partly intended to reassure more conservative international and domestic forces. Norway, whose former prime minister now runs Nato, was understood to be particularly anxious about Scotland pulling out of the alliance, as were some Scots.

“The Nato shift was sold as ‘we will be more credible in an independence campaign’,” McAlpine from Common Weal explained. “I was one of the leading folk in a campaign to stop that happening from outside the party. We were asking how they’re going to get rid of the nukes but stay in Nato. Nato is never going to let that happen.”

When the SNP voted at its conference to support Nato, reversing 30 years of opposing the alliance, two MSPs quit the party in protest, with one ending up at the Greens.

“Nine years ago there was a flashpoint, and it was very much from the activist side of the SNP who came over to us and were much more comfortable campaigning with us,” Greer reflected. “At the core of it, Nato’s a first-strike nuclear alliance. So it’s a simple, moral principle that folk have. They could never sign up to it.”

Scottish CND said the SNP’s shift to Nato was also a “huge worry” at the time, but activist pressure resulted in renewed pledges from the party’s leadership to scrap Trident. However, Mackenzie fears that the leaders of a newly independent Scotland would come under “enormous pressure” from Nato to allow the UK to keep its Trident submarines on the Clyde.

“There’s a range of options there. One of them is the kind of long-term Guantanamo, a never-ending lease,” he said, referring to the US navy annexing parts of Cuba’s coast. Britain is familiar with such a strategy, having refused to return large areas of Cyprus after independence and retaining them as so-called sovereign base areas.

“And then there’s various shades in between, like we’ll give them a short lease,” Mackenzie cautioned, before striking a more optimistic tone. “What we’ve been stressing very strongly is the role of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in all of this. I don’t think it’s been properly understood, even in Scotland.”

The treaty, which entered force in January, makes it illegal for signatory states to possess nuclear warheads and puts them in the same class as other inhumane weapons such as land mines, clusters bombs and chemical weapons.

Britain is not among the 54 states that ratified the treaty at the UN General Assembly, and has further snubbed the signatories by announcing plans to increase the number of warheads in its Trident arsenal. But an independent Scotland could well sign it, with figures such as the SNP’s former chief whip, Bill Kidd, being highly supportive of the initiative.

“A key question for independent Scotland is, do we ratify the treaty?” Mackenzie asked. “Once you ratify the treaty you don’t only have the right to get rid of the weapons, you have an obligation and you have the backing of international law.

“The beauty of that first move is that it also puts the Nato question in its proper place. Let’s commit ourselves to this treaty, so we have no obligation but to get rid of these weapons, then we can look at the Nato question.”

Atlanticism

While the nuclear ban treaty may strengthen the SNP’s hand when it comes to negotiating the removal of Trident from Scotland, some still believe the party’s embrace of Nato was part of a wider compromise within Scottish radicalism.

For the Greens, the issue is not just Nato’s nuclear doctrine.

“Look at Turkey,” Greer said. “It is Nato’s second largest military and it is under the control of an autocrat, who is perfectly happy slaughtering his own civilians. I can’t ignore the fact that Nato soldiers herded 100 people, mostly women and children, into a basement and set the building on fire.”

Turkish forces stand accused of killing up to 160 civilians during a siege of Cizre, a majority Kurdish town, in 2015-16, as part of a campaign by its authoritarian president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to stamp out demands for Kurdish autonomy in the east of the country.

“Turkey commits genocide against the Kurdish population,” Greer commented. “That’s a Nato force doing that and not being held to account by Nato. So if the argument for Nato is an alliance based on the defence of democratic nations and collective freedoms, it’s not demonstrating that.”

On top of the human rights record of some Nato members, there are worries that the SNP’s support for the alliance came as part of a broader turn towards a pro-US “Atlanticist” foreign policy – a sharp contrast to the days when Alex Salmond led opposition to the war in Iraq.

“If you think the UK wasn’t taking an interest in the SNP’s foreign policy stance as a backup, then I think that’s utterly unrealistic,” McAlpine told me. “The UK foreign policy establishment was lobbying certain figures inside the SNP on this issue [Nato]. There were a tiny number of flat-out pro-Atlanticists – people who had this as a hobby horse.”

McAlpine blames the SNP’s former defence spokesman Angus Robertson for pushing through the policy switch on Nato in 2012. “It was purely Angus Robertson. He went to Aberdeen University’s foreign policy department, which is notoriously Atlanticist. He said to me that he’d been assured by UK foreign policy establishment types that they’d be less hostile to Scottish succession if we played nice and stayed in the family.”

But playing nice can make Nato members take part in military operations they might prefer to avoid, even if it offers protection from Russia. A Westminster committee heard evidence in 2013 from Ole Kværnø of the Royal Danish Defence College, who said Denmark had fought in Afghanistan to keep “our preferred partners happy so that they will come to our rescue at the end of the day”.

Greer sees such moves by the SNP as part of a pattern: “Nicola Sturgeon gave a speech to the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington DC a couple of years ago, where she said something like an independent Scotland and the SNP would mirror 95% of the UK’s foreign policy positions.

“For a lot of folk in the SNP who’d hung in there until that point but didn’t like this gradual move towards the centre, this was another of those flashpoints. We had a wee influx of folk joining us because our more principled anti-Nato position – the one that the SNP had previously held for decades – was the one they still held on to.”

More recently in March, two of Sturgeon’s senior colleagues wrote an op-ed for the Washington-based Foreign Policy magazine, titled “An Independent Scotland Would Bring No Surprises for Allies”, and promised to be part of “a global A-Team”.

Battle of the bots

McAlpine fears that in the absence of any group in Scotland advocating an alternative to Atlanticism, it could become the default approach to foreign policy under independence. “You can pretty well work out where the SNP will be positioned politically if you just close your eyes and imagine what a Guardian editorial will say,” he commented, criticising the UK’s leading liberal newspaper which consistently supports foreign interventions by Washington.

“We’ve lived in Atlanticist Britain for so long we’re not even aware of other foreign policy stances. There’s plenty of people who have a strong view on a given thing: Trident, Palestine, the arms trade. But you won’t find in Scotland organised bodies outside university departments that have anything like what you might call an organised world view,” McAlpine said.

As a result, he worries that the leadership of Scotland’s independence movement are out of touch with grassroots attitudes towards international affairs, telling me: “The SNP’s foreign policy stance doesn’t reflect the views of its members, ever since the NATO shift.”

For him, the starkest example of this divergence is the SNP leadership’s claims that Russia is interfering in the Scottish independence debate.

“My head’s burning with the madness, the sheer western insanity of this crazy conspiracy theory that it’s Russia, it’s all Russia,” which is behind the rise in support for Scottish independence.

McAlpine asked: “What is the SNP doing claiming Russian state intervention? That was a British state invention to once again explain how the liberal establishment was losing its grip on democracy. Everybody knows this. And there are plenty of people in the independence movement scratching their heads going, ‘What, in the name of God… what possible reason are we giving credulity to this nonsense?’”

Last year, the SNP’s former deputy leader, Stewart Hosie MP, who sits on Westminster’s intelligence committee, endorsed a highly anticipated report on Russia. It said there was “credible open source commentary suggesting that Russia undertook influence campaigns in relation to the Scottish independence referendum in 2014”. But, as evidence, the report cited only a study on “Pro-Kremlin Trolls” compiled by a former Nato press officer.

The so-called Russia Report amplified broader concerns about interference in UK politics by Kremlin-funded Twitter bots and media organisations like Sputnik and RT, whose stars include Alex Salmond. But the TV channel also has a show hosted by George Galloway, another former MP who is actively campaigning against Scottish independence.

Despite the obvious contradictions in RT’s masterplan to break up Britain, Hosie is not alone in his concerns about Russian meddling. Last year the SNP’s foreign affairs and defence spokesmen at Westminster, the MPs Alyn Smith and Stewart McDonald, together received £3,700 worth of flights and hospitality from a US government-backed think tank, the Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars, to participate in a workshop in Washington DC on “defeating disinformation”. Smith and McDonald did not respond to my requests for an interview.

MacAskill is also dismayed with the stance his former SNP colleagues have taken on the issue. “I think that’s all craziness,” he told me. “I’m not a fan of President Putin, equally I’m not for having a new Cold War. So it’s about getting the balance right, which other nations seem to do – but some of my former colleagues in the SNP and the current British government want to go back to the days of the 1980s.

“Having lived through there and how close we came to obliteration by accident, I don’t want to go back there. We need to defuse and have diplomacy, not sabre-rattling.”

Despite his historic support for the SNP’s switch toward Nato, MacAskill is sceptical of the alliance’s air policing missions which see British Typhoon fast jets stationed in the Baltic and eastern Europe.

“I remember when they put British aircraft in Estonia. I have a friend over there, a Scot married to an Estonian who is ethnically Russian. She was saying she could not persuade her family back in Russia that this was anything other than preparing for an attack. Memories of Hitler and Napoleon have scarred the Russian psyche.”

The Scottish Greens also want to avoid a return to the Cold War. “The threat Russia poses today is not the threat Russia posed in the 1980s,” Greer told me. “But if we are serious about strategic alliances to counter the threat posed by Russia, we should do that through economic measures.

“The single most effective way that you tackle Russian influence head on would be to finally deal with money laundering in the City of London, because the Kremlin connections to a huge amount of that money laundering are obvious. That’s what you do about the security threat posed by Russia – military arms races don’t do that; antagonistic posturing doesn’t do that.”

McAlpine put it more bluntly. “Russia and the UK are in a cock-measuring competition. Scotland isn’t measuring its cock.”

All at sea

The debate over the threat posed by Russia does matter. The assessment will partly determine an independent Scotland’s defence budget, and whether Edinburgh can in future get away with spending less on the military than Scots now do as part of the UK.

Britain currently has the fourth largest defence budget in the world at £44-billion per year, spending more than Russia on its own. The SNP, although vague on its future defence plans, said in 2013 it expected to spend £2.5-billion annually, compared to around £3.3-billion that Scottish taxpayers were then contributing to the UK’s military.

Such expenditure would put Scotland roughly on a par with Denmark, which has naval frigates, fast jets and around 8,000 professional soldiers. McAlpine is confident Scotland could safely slash military spending even further.

“Are we seriously talking about a Russian invasion? It’s gibberish,” he tells me. “There hasn’t been a proper UK navy patrol in Scottish waters in about 30 years. Just before the last independence referendum, a Russian military vessel strayed into Scottish waters,” McAlpine recalled, referring to the Kremlin’s ageing Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier anchoring near the coast. The Ministry of Defence learnt about its arrival not through maritime surveillance, but on social media.

“If the Ministry of Defence was seriously concerned about that, we’d have a substantial shipping presence up there,” he argued. “We wouldn’t have boats in the Middle East.” During the last decade, Britain opened two new naval bases in the Gulf, and is sending one of its new aircraft carriers on a patrol of the South China Sea.

“There is no logical reason for the UK’s obsession with aircraft carriers for a nation of our size,” McAlpine commented. “That kind of power imposition doesn’t make sense. Germany doesn’t have them.”

Instead, a report by his Common Weal think tank identifies the main threats to independent Scotland as organised crime and cybersecurity. He says these could be dealt with by the police and coast guard, rather than an expensive navy and fast jets.

“Most of the world doesn’t have a particularly offensive defence capacity,” he commented, pointing to some of its neighbours. “Left to its own gravity, Scotland would, I believe, veer heavily in the Sweden/Ireland direction. But the only political party which takes a Scotland-specific stance on foreign policy matters is the SNP, and it’s been captured.”

Although McAlpine is concerned that MOD-funded think tanks like the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) have lobbied the SNP leadership into hawkish Atlanticism, there is agreement among them that an independent Scotland could have a relatively small military.

In 2013, RUSI’s deputy head, Prof Malcolm Chalmers, told a Westminster committee investigating the issue that: “It is possible that an independent Scotland, looking at how difficult transition would be, would adopt the Irish option.”

The committee commented that Ireland – whose neutrality and annual military budget of just £0.7-billion is admired by Scottish CND – has “a small territorial defence force, with a navy that patrols its coastline, and a minimal air force”.

It added: “Ireland takes part in peacekeeping roles, but does not retain the capability to deploy substantial forces away from Ireland.”

Chalmers felt the Irish model might become inevitable for Scotland. Even if the country were to inherit a share of the UK’s frigates and fast jets, the running costs of such sophisticated equipment would be higher than the SNP wants to spend on defence.

Prof Ron Smith from Birkbeck University made similar points to the committee: “For a country of five million to spend £2.5-billion on defence, with armed forces of 15,000, it is perfectly understandable and seems quite reasonable in a steady state. The real difficulty is going to be getting there from here, because most of the equipment they inherit will be inappropriate.”

Arms industry

Scotland has a domestic arms industry which could be capable of meeting some of its own defence requirements, or secondhand equipment might be sourced more cheaply from countries like Sweden and the US.

However, Scotland’s arms industry has courted controversy in recent years for exporting weapons to conflict zones. Giant US arms corporation Raytheon has a missile factory in Glenrothes, Fife, that supplies the Saudi air force bombing campaign in Yemen, where thousands of civilians have died.

Although the SNP has heavily criticised UK arms sales to Saudi Arabia, the Scottish Greens accuse it of hypocrisy, as the SNP-run Scottish government is giving taxpayer subsidies to arms factories such as those run by Raytheon.

Greer told me: “You have a party who at Westminster is criticising the fact the bombs are being dropped with British support, but in Edinburgh are writing cheques to the companies making the bombs in Fife.”

“There are valid discussions to be had about quality industrial jobs in places like Glenrothes,” Greer added, “but Raytheon are a multibillion dollar international arms company and when people find out that Scottish taxpayers’ money is being given to them, the anger there is palpable. Not just because they think it should go to local businesses, but there is a strong desire to behave responsibly internationally, people get it.”

Police training

The SNP also criticises the British government for training security forces that are involved in human rights abuses. However, they are less willing to reflect on their own role in similar controversies, casting doubt on their commitment to a more ethical foreign policy in the event of independence.

The Scottish Police College already has its own “international development unit”, and from 2012 the SNP-led government in Edinburgh had the power to authorise the deployment of police instructors overseas.

Since gaining the power, SNP ministers have authorised 90 police deployments to Sri Lanka, a country that is notorious for torture and where a government minister recently said “everything will be fine” if its president – who is accused of war crimes – acts more like “a Hitler”.

Despite years of concerns in the Scottish press about Sri Lanka’s treatment of its Tamil minority (many of whom want a separate state), the SNP’s justice minister Humza Yousaf has repeatedly dismissed calls for the Scottish police training to stop.

When I raised the issue with Yousaf’s predecessor, MacAskill, he was surprisingly apologetic and wanted to “atone” for not stopping the Sri Lankan scheme when he was a minister.

“You’re right, it’s something we need to take action upon,” he told me. “It’s something that’s slipped by in Scotland… it occasionally appeared in the papers. I have to say, as a former justice secretary, I was oblivious to it.”

“I don’t think it’s a matter of powers, it’s a matter of will or a matter of awareness. Something that’s a problem in Scotland is we think we don’t do these things, and then actually what you do is deliberately turn a blind eye. Yes, we do. We would criticise it if it was Sandhurst training El Salvador and Guatemalan police units.”

MacAskill did have some concerns about the training of foreign forces taking place at the Scottish Police College when he was justice secretary. “There was a chap from Hong Kong who was asked what he would do if there was a threatening crowd outside the building and he said ‘we’d release the sniper’.” Upon hearing this story, MacAskill asked the commander of the college, “What are you doing training the likes of this?”

China

On the question of how a small state like Scotland should handle rising superpowers like China and the threat of climate change, McAlpine offered the most far-reaching solution.

“A lot of foreign policy assumptions are farcical,” he commented. “It’s about maintaining stability but creating massive inequality for the purpose of protecting long supply chains. It’s why we’ve got all these tankers travelling around the sea.

“So we should lead the way in de-globalisation and create a Scottish model where people can look to Scotland and see, actually you can shorten supply chains and maintain or improve quality of life, and have less reliance on parts of the world where we are fuelling conflict because of our reliance. We don’t need to be in a war with China.”

His views may find a receptive audience after a year in which the Suez Canal was blocked for days by a single ship drifting off course, and the difficulties during the coronavirus pandemic in importing personal protective equipment from China.

“Plus climate change ain’t going to hold up,” he adds. “We are going to see massive disruption in food supply chains in the next 50 years – it won’t take that long. So I would de-globalise. Everybody in the world has to take more responsibility for the production of domestic consumption.”

McAlpine agreed that goods made in Scotland would cost more, but argued the jobs they created would give workers more money to spend while reducing Scottish reliance on sweatshops in China.

“We need to accept that things will get a bit more expensive in future,” McAlpine said. “We need to reduce economic inequality so we don’t have to shave sixpence off at the mall, because all of that price suppression is based on externality production.”

He concluded: “It seems to me we should live more locally, live within your means, live more within your local biosphere. That’s what the planet is telling us. It’s not telling us there’s an environmental crisis, fly to Davos to discuss it.

“So that’s where I see a really positive role for Scotland, if we maintain cultural engagement but reduce economic engagement, an awful lot of the harmful negative imperatives of UK foreign policy would reduce.”